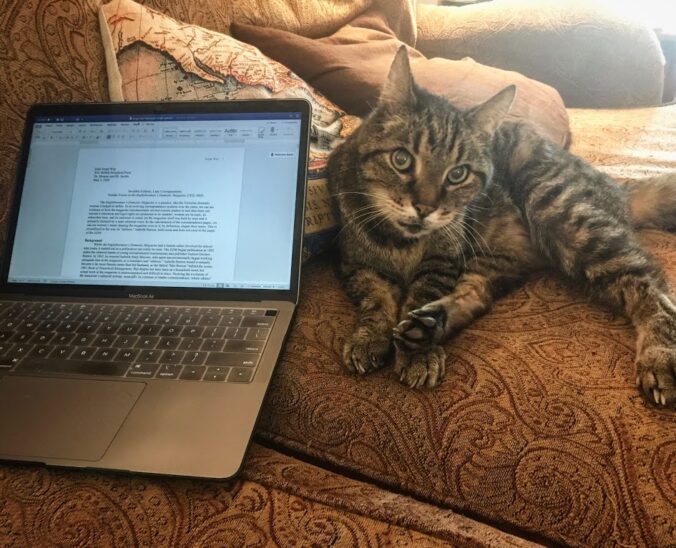

During my dissertation process, but also in my other writing, one tip that has really helped me when I’m in the middle of a big project is to “park downhill.”

Although I can’t yet nail down an original source for this concept (if you’ve got one, let me know, and I’ll update this!) here are the ways it has worked for me:

To me, parking downhill means that when I am at a stopping point in a large project, I always try to pause for the day in a way that will make it easy to get started again.

This could mean:

- Leaving myself a note with very specific details about what I was about to write next

- Marking my notes-to-self in an easy-to-search way (I like @@ or */, just as an example)

- Starting with something “fun” or pleasant rather than something I have anxiety about

And here are some other writers’ thoughts on parking downhill:

What is the best writing advice anyone ever gave you?

Park downhill. I can’t remember who passed along this piece of advice — one of my former editors at The San Francisco Chronicle, who inherited it from someone else, I’d bet — but the sentiment has stayed with me. The idea is to stop while you’re ahead, to close up your laptop and end the work day when you have an idea of where you’re headed next. It makes picking things up the next morning that much easier. You’re excited and know what you want to write next — versus feeling stuck and staring blankly at your cursor for an hour, then deciding that you really should just go walk the dog, or wipe down the counters, or write that letter to your great-aunt or…. you get my gist.

Lizzie Johnson, Washington Post Reporter (source)

Parking on a downhill slope eases the transition into work because you’re not starting your session with a dreaded task, but an interesting one. It’s easy to start your work. You want to start.

Jeffrey Windsor, Professor (Source)

‘Park downhill: at the end of the day, leave a sentence or paragraph or piece unfinished so you don’t wake to an empty screen.’

In my own writing life, I call this useful tidbit of advice: “Inviting your future self to take a seat.” Before I finish writing for the day, I write an invitation to my future self to take a seat the next day and write. I don’t mean a persuasive letter or note to myself to entice me into writing. I mean tactics like writing a topic sentence containing one idea, offering me an easy lead-in for starting a new paragraph the following day.

I also find leaving a question to answer about my data or the literature works well too as a jump start. ‘Anchor sentences,’ or incomplete sentences that I need to tie off, give me an equally effective gravitational pull to my writing seat every morning.

Ed Yong, Science Writer (Source)

I hope this tip is helpful for some other folks who may, like me, find large writing tasks daunting at times. Bit by bit, it really helps me to keep that momentum going, and leads to solid progress.